by the late Mark Sullivan, Board Certified Criminal Defense Attorney, Palm Springs, California. Originally printed in 2005 and reprinted with permission from Crime, Justice and America magazine

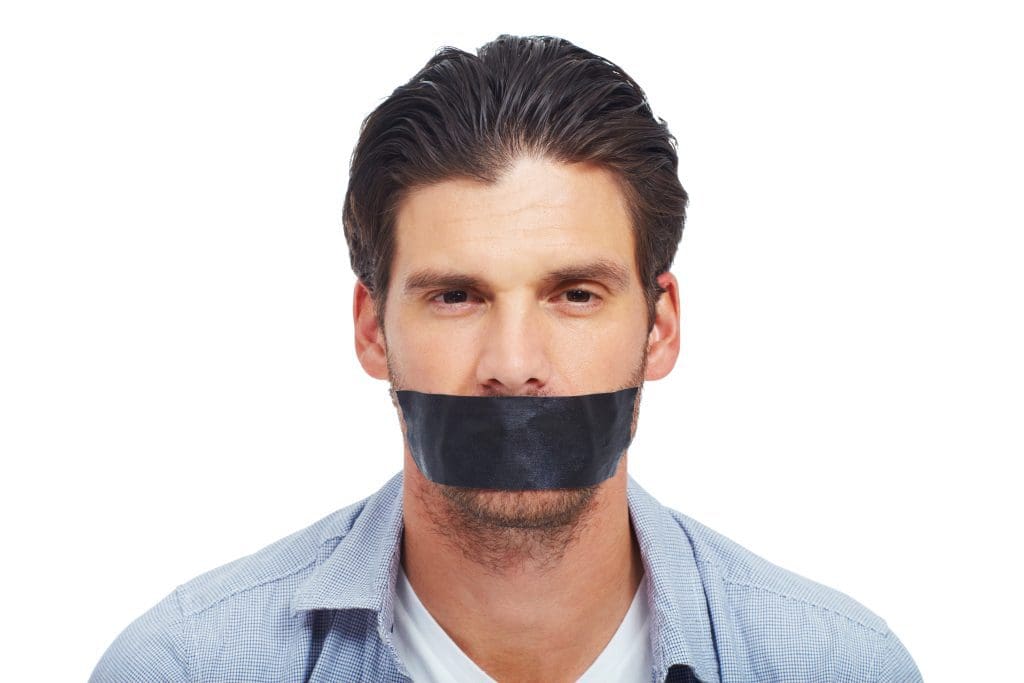

This article might just as well be entitled “You have the right to remain silent. Use it. Say nothing.”

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

This doesn’t mean “Deny having committed the crime.” It means telling the police officer that your attorney has advised you not to answer any questions, and then saying nothing else to anybody until you talk to him or her.

Recently I was giving this advice to a potential witness, and he said, “I’ll just tell them that I don’t know anything.” This is wrong. For one thing, he did know something, so this would have been a lie. I may have wanted that witness to testify at the trial. A competent prosecutor would have discredited the witness by showing that at one point, he’d told the police he didn’t know anything, and at trial he was trying to convince the jury that he did know something.

ONE – What If The Police Don’t Read You Your Rights?

You always have the right to remain silent. Do not be confused by the fact that sometimes they’re, the police don’t read you your rights. Sometimes they are required to, and sometimes they’re not. But any time you are questioned by the police – whether you are under arrest, or only being detained, or you are just a witness – you always have the right to remain silent, even if the police don’t tell you so. Until or unless a judge from a court of competent jurisdiction orders you to answer questions, you have the right to remain silent. Use it. Just politely tell the police that your lawyer told you not to answer any questions.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

And understand that even if you’re not asked a question, the prosecution can and will use anything you say, even to a friend or family member. A client of mine asserted his right not to answer a police detective’s questions, but spontaneously asked whether he could get the death penalty. The court allowed his question to be used as evidence against him. Say nothing.

TWO – Do Not Talk To A Clergyman, A Therapist, Or Your Spouse

Don’t say anything to anybody other than your lawyer. That means nobody. You should not discuss your culpability with a clergyman, an advisor, a doctor, a therapist, a counselor, or your spouse. Under certain circumstances, any of them could be required to testify about what you said to them.

In a child abuse or neglect situation, for example, a psychologist or a counselor may be required to report what you say to the authorities, even if he is not questioned. If you admit to your therapist that you had inappropriate contact with a child, the therapist must report the conversation to the authorities.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

Clients often ask, “Can’t a wife refuse to testify against her husband?” Not always. Not even usually. The bottom line is, say nothing to anybody other than your lawyer.

THREE – Isn’t Refusing To Answer Questions Admitting Guilt?

My clients ask me whether refusing to answer the police’s questions isn’t just going to convince them they have something to hide, and are therefore guilty. “Won’t they arrest me if I don’t cooperate?”

Sure, the police might think you’re guilty if you refuse to answer. And yes, they may arrest you, although it is rare for somebody to be arrested simply for failing to cooperate. On the contrary, the police know that once you exercise your right to remain silent, their case against you just got weaker. Why else would they be so persistent? So the likelihood of your being arrested is actually lower if you invoke your right to remain silent than if you cooperated with them – though it could happen.

So yes, the police might think you’re guilty. So will the prosecutor. But I’m not worried about what they think. The police can’t convict you. Neither can the prosecutor. In fact, neither can the judge. In a criminal case, the only way you can be convicted is if a twelve-person jury unanimously decides that the prosecution has proven you guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. And the jury only hears admissible evidence.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

What does this mean? It means that a jury will never hear that you refused to answer a police officer’s questions. Since remaining silent is a Constitutionally protected right, there is no evidentiary value in the fact that you exercised it. And since a jury might infer guilt if they knew about it, the prosecution can’t mention it.

FOUR – Why Not Deny It?

Some of my clients ask, “I can understand why you tell me not to admit having committed the crime, but I didn’t admit it. I denied it. What is so wrong with that?” Denying it is exactly what the police want you to do (second only to admitting it, of course, which allows them to wrap up their investigation without doing any more work). By denying that you committed the crime, you are choosing and disclosing the nature of your defense:

- before you know the evidence against you;

- before you have the opportunity to calm down and thing rationally; and

- before you’ve consulted with an attorney and know the law

FIVE – You Have Not Seen The Evidence Yet

I always use the Mike Tyson example when I talk about this. You maybe remember that back in the early 1990s, the heavyweight boxing champ was accused of taking a young woman – a beauty contest contestant – back to his hotel room and raping her. The woman waited a day or two before reporting it.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

By the time the police started to act on the report, there wasn’t much physical evidence to be examined: She had already bathed, and underwear, clothing, towels and bed linens had all been laundered. It got worse for the prosecution, as they discovered a potentially devastating piece of evidence.

Nonetheless, they subpoenaed Tyson to appear before a grand jury. Of course, as the target of the investigation, Tyson had the right to invoke his 5th Amendment rights; but like most accused criminals, Tyson was eager to clear his name.

Had I been his lawyer, I would have told him that he had the right to remain silent. Use it. Do not assist the prosecution. The only time he would tell his version would be if he needed to testify, as the final witness for the defense. That would have been after the prosecution had divulged all its evidence, and had presented their case to the jury, without having had the opportunity to hear Tyson’s side of the story, and leaving them no time to investigate or refute his version of the events.

In one of the worst cases of professional malpractice imaginable, Tyson’s lawyer allowed him to testify that he’d had sex with the young lady, but that she had fully consented.

Tyson and his lawyer had fallen into a horrible trap, and Tyson had convicted himself: The problem that the prosecution had discovered early in the investigation was the testimony of the woman’s roommate, that the victim had told her, “That son of a bitch tried to rape me!”

“Tried”?

Maybe the victim had inserted the word by mistake, in the excitement of the moment; or as a result of the trauma she’d suffered. Or maybe she hadn’t used the word at all, and the roommate had heard her wrong. Nevertheless, when the prosecutor came across the statement, he knew that any capable criminal defense lawyer could have won the case without even calling one witness. He could probably hear the defense’s closing argument vividly:

“There was no evidence that they’d ever had sex. No physical evidence. No evidence of bodily fluids, no soiled undergarments or bed linens, and no witnesses. Nothing. And there was the long delay in the alleged victim having reported the alleged crime. Why?

“Obviously they never had sex; because if they had, she wouldn’t have said that he tried to rape her. He easily could have forced himself on her if he’d tried. If he forced himself on her, she would have said that he’d raped her. The young lady is obviously confused. The first and most important element of the charge of rape, the act of sexual intercourse, is unproven. There is no need to go any further.”

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

But Tyson’s lawyer never got that opportunity. By the time he learned what was contained in the police reports – after the grand jury testimony – Tyson (with his lawyer at his side) had already convicted himself. He admitted the first element of the charge, sexual intercourse. So the blockbuster statement attributed to the victim by her roommate, that she’d heard the victim say “tried”, turned out to be a non-issue.

All because a defendant thought that if he denied having committed the crime, he was going to help himself. Remember this is you ever think of waiving your right to remain silent and denying your involvement in a crime.

SIX – You Are Too Emotional

Here is another example – a rape case of mine – where a suspect helped the prosecution by panicking and speaking too soon, denying something easily proven: While on a business trip, a man called a local escort service for some female companionship. A girl came to his room, and eventually they had sex. There was a dispute over the amount of compensation; and when she returned to the escort service’s office, the girl reported that she’d been raped.

The police were skeptical of her accusation because they knew that escorts from that service did engage in sex for money. Her story was that she was only there to strip – and as she was doing so, he picked her up and raped her.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

So to get his version of what happened, the police made an unannounced visit to his hotel room. They woke him up, and asked him whether he’d called an escort service earlier in the evening. A married man, he was overcome by guilt and fear, and claimed that nobody had been there that evening except for himself. This was easily disproved, of course, through physical evidence and phone records. The man had completely destroyed his own credibility, and added credence to the prostitute’s story.

Had he said nothing, and remained silent until he knew the accusation and the evidence against him, he most certainly wouldn’t have been charged. All the police wanted was to see whether the prostitute’s story was believable. When he denied that she’d been there at all, suddenly they had what they thought was a much stronger case against him. Ultimately, he had to explain to a jury why he’d lied to the police.

Fortunately, our investigation led us to other escorts from the same service, who testified that she’d told them she’d lied about the incident because he hadn’t tipped her generously enough; and she was going to find a way to get more money from him one way or the other. We won the case, but it was a terrifying ordeal for our client to have to wait for hours for the jury to finish their deliberations and acquit him.

SEVEN – You Do Not Know The Law

An example of this factor involves a landlord who was accused of threatening and terrorizing a deadbeat tenant. The landlord agreed to undergo questioning because he was certain he had nothing to hide. According to him, not only had he not threatened to kill the tenant and his family, he’d acted in a perfectly legal and appropriate manner to try to collect a debt. He said that he’d merely told the tenant that he would not report him to the police is he paid him the money he owed him.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

Unfortunately for the landlord, by waiving his right to remain silent and telling his story, he confessed to having committed the crime of extortion. Yes, he denied committing any terroristic threats; but he admitted threatening to accuse a person of a crime unless he was given money, and that constitutes the crime of extortion (or blackmail).

Had the landlord consulted with a lawyer before answering any questions, he would not have said anything, and would not have convicted himself.

EIGHT – Why Prepare The Prosecution For You Defense?

The most important procedural right of the defense is that we get to go last. The prosecution has to put on its entire case before we have to present any evidence. They have to disclose their entire case before trial. And with a few exceptions, the defense has to tell them nothing. Why would any defendant want to waive this enormous advantage? Why give the prosecution a chance to mold their case to take advantage of any weakness in your defense? It’s the defense’s right to mold its case around any weakness in the prosecution’s case.

Let the prosecution hear your case for the first time when they are least able to act upon it, at the same time the jury hears it, and just before the case is submitted to the jury for a verdict.

NINE – Are The Police Allowed To Monitor Calls?

Yes. In California and most other states, the police may monitor and record private telephone conversations. If you are ever concerned that you might be accused of a crime (especially a sex crime), do not discuss the incident over the phone. When an alleged victim of a sex crime reports the incident to the police, the police often set up a “pretext call”: having the alleged victim, for example, call the suspect wanting to discuss their having had sex in the past. She may tell him that she is in pain, or angry or disappointed in him for what he did, or say that she needs something such as money for medical expenses. These calls are monitored and recorded by the police, who hope that the unsuspecting suspect will unwittingly admit to the commission of the crime.

If you ever believe you may be the target of a pretext call, you should not accept it. If you are already on the phone, you should say that you need to talk to your lawyer before saying anything. And then you should hang up and call your lawyer immediately.

TEN – Jailhouse Snitches

If you are in jail, never discuss your case with anyone: especially a fellow inmate whom you don’t know. Jail is the worst place to make new friends: Unscrupulous inmates will pretend to be very sympathetic, and claim to hear what you want to say about your case, and then offer to sell your statements to the prosecution in exchange for breaks on their own cases. This reprehensible conduct is allowed by law.

-

Attorneys.Media

-

@attorneys_media

-

linkedin

-

Digg

-

Newsvine

-

StumbleUpon

Remember also, telephone calls made from jail and conversations during jail visits – even with your spouse and family – are tape recorded and monitored. Evidence of these conversations is also admissible against you in court.

ELEVEN – Should You Ever Apologize?

Usually not, at least not until the case is completely resolved. Be sure to ask your lawyer about this if you are in doubt.

Not long ago in a local courthouse, a female lawyer abruptly left a judge’s chamber after the jurist allegedly groped, kissed and fondled her against her will. This judge, who had 20 years experience handling a criminal calendar, presumably knew the difference between provable cases and those which result in acquittals. But in response to her rebuking his advances, and without thinking of the consequences, the judge actually called the young lady intending to apologize; and when he did not get through to her, he left voice messages on her phone pleading with her not to report him to the authorities!

This is more than just an example of how stupid I have always known this judge to be. It is an example of how one must remember the advice in this article. Had the judge calmly analyzed the situation, he would have realized that the young lady’s word against his would not likely to have been enough to convict him. There were no witnesses, and there was no physical evidence. He should have said nothing. Instead, he convicted himself when he apologized to her and asked her not to report the incident.

Yes, even experienced legal minds can slip up sometimes. It is difficult to remember to remain silent. Just remember, when the police ask you if you are willing to answer their questions… JUST SAY NO!