How Pay Stubs Can Protect Employers and Employees in Legal Disputes

This article is for general information only and is not legal advice.

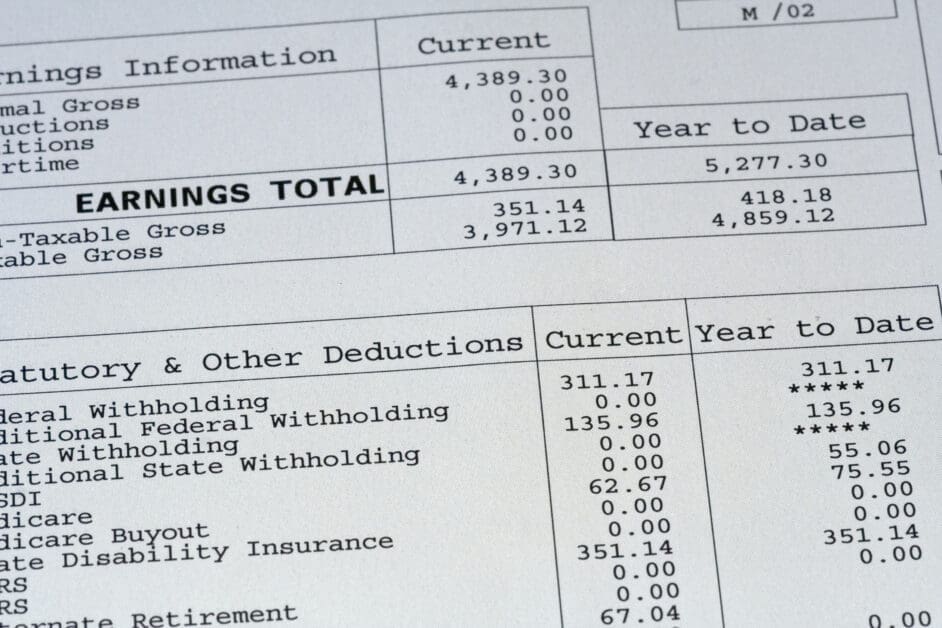

When workplace disputes arise, the side with the best records usually has the upper hand. Few records are as contemporaneous and therefore as persuasive as a properly prepared pay stub. Whether the issue is unpaid overtime, improper deductions, final wages, or taxes, accurate pay stubs serve as a ledger for each pay period, memorializing what was earned, what was withheld, and the reasons for each. In litigation, arbitration, government audits, and pre‑suit negotiations, that level of detail often becomes the backbone of a winning case or a swift, favorable settlement.

Why pay stubs matter as evidence

Pay stubs corroborate the specifics that wage-and-hour cases turn on: the applicable rates, the number of hours paid at each rate, and the deductions taken. In unpaid wage lawsuits, plaintiffs’ counsel frequently begin by collecting stubs to demonstrate patterns (for example, no overtime premium despite regular 50-hour workweeks). Defense counsel, in turn, rely on consistent, compliant stubs to demonstrate that the employer calculated wages correctly and made only lawful deductions. Courts and agencies view them as reliable because they are created in the ordinary course of business near the time of payment. Law firm guides for workers similarly list pay stubs among the first items to gather for unpaid wage claims, underscoring their central role as proof.

Recordkeeping rules: what the law expects you to keep

Federal law sets the floor for payroll record retention. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), employers must keep payroll records for at least three years, and keep the supporting documents used to compute pay (such as time cards and schedules) for two years. These records must be available for inspection by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL).

Tax rules add another layer. The IRS advises employers to retain employment tax records, think Forms 941, W‑2/W‑3 data, and withholding details for at least four years after the date the tax becomes due or is paid. In practice, that means your payroll and pay stub data should be archivable long enough to satisfy both wage-and-hour and tax retention timelines.

State laws can be stricter. California, for example, requires employers to furnish itemized wage statements and to retain copies for at least three years; failing to do so can create statutory exposure even apart from underlying wage claims.

Digital or paper? Make sure stubs are accessible

Electronic wage statements are widely accepted so long as employees can actually access and print them and, in some jurisdictions, elect to receive paper copies. California’s Division of Labor Standards Enforcement has long recognized electronic statements on those conditions. For employers, that means your payroll system should ensure secure access, exportability, and a clear audit trail.

Disputes where pay stubs make the difference

- Unpaid overtime and minimum wage. Itemized stubs that show hours at straight time and at overtime rates help verify that premiums were paid correctly. When they don’t, plaintiffs can use the stubs themselves to quantify the shortfall across pay periods. Employers can pair compliant stubs with time records to show proper calculations.

- Illegal deductions and chargebacks. Detailed deduction lines (benefits, garnishments, advances, tools/uniforms where permitted) prove what was withheld and on what authority. This clarity can stop a small wage dispute from spiraling into a broader unfair‑practice claim.

- Final wages and waiting‑time penalties. Stubs for the last pay period document what was paid at separation and whether accrued, earned amounts (e.g., certain bonuses or PTO where required by law or policy) were included.

- Misclassification claims. For alleged “exempt” employees, consistent salary entries and absence of hourly overtime lines won’t decide the case, but they frame the narrative and interface with job descriptions and time records.

- Tax audits and government investigations. Harmonizing stubs, payroll registers, and filed tax forms reduces exposure and administrative burden during IRS or DOL reviews.

What a litigation‑ready pay stub should include

While the exact requirements vary by state, a defensible, employee‑friendly pay stub typically includes:

- Employer name and address, and employee name and unique identifier

- Pay period start/end dates and pay date

- Total hours worked at each rate (regular, overtime, double time where applicable)

- Rates of pay and line‑item extensions (hours × rate)

- Gross wages, itemized deductions, and net pay

- Year‑to‑date (YTD) totals for wages and deductions

- Accrual balances when required by state law (e.g., certain paid sick leave disclosures)

Think of the stub as the employee’s summary ledger for the period. Consumer financial education sources emphasize the same core components, which is why employees and lenders treat pay stubs as foundational documents for verifying income.

Best practices to strengthen your position on either side

For employers

- Align retention schedules. Keep payroll records at least three years (FLSA), supporting pay‑calculation records two years, and employment tax records four years. Many employers standardize on a four‑year+ retention policy to cover all bases.

- Standardize itemization. Configure payroll software so every deduction and earning type is clearly named and consistently displayed.

- Enable access. Provide a secure self‑service portal or a reliable process to furnish copies promptly upon request; some states mandate it.

- Audit regularly. Periodic internal reviews spot mis‑coded earnings, missing overtime lines, or benefit deductions that continued post‑termination issues that often seed class actions.

- Litigation holds. When a dispute surfaces, suspend routine deletion and preserve relevant stubs, time data, and payroll exports to avoid spoliation arguments.

For employees

- Save each stub. Keep your own copies (digital or paper). If a discrepancy arises, a personal archive speeds resolution and strengthens your claim.

- Check the math. Verify hours, rates, and deductions every pay period; raise issues in writing so there’s a record.

- Use stubs as proof of income. Beyond wage claims, stubs help with loan applications, child‑support modifications, and unemployment eligibility.

The bottom line

Well‑crafted, compliant pay stubs don’t just keep payroll running they keep disputes from escalating and give judges, juries, and agencies trustworthy, contemporaneous evidence. Employers that invest in clear itemization, accessible delivery, and proper retention reduce legal risk and administrative cost. Employees who review and retain their stubs gain leverage and clarity when something looks off. In litigation, precision beats memory; the humble pay stub often supplies that precision.